Defective Ball

Problem

You have 12 seemingly identical balls, but one of them is defective: it is either heavier or lighter than the others (you do not know which). Using a simple balance scale that tells you only which side is heavier, determine which ball is defective and whether it is heavy or light, in just 3 weighings.

Hints

Hint 1

Think about how you would solve a very small problem: suppose you had 3 balls, where you suspect that ball 1 and ball 2 might be light and ball 3 might be heavy. How could you identify the defective ball in just one weighing?

Hint 2

Now level up to 9 balls where you know one is heavier than the rest. Try to solve that in 2 weighings. Notice the pattern of splitting into three equal groups and isolating the odd one.

Hint 3

The pattern is to divide the balls into three groups of equal size, and keep applying the weighing to eliminate 2/3 of the possibilities until you hit a base case you can finish.

Hint 4

However, for the 12-ball problem it is trickier: after the first weighing, you must mix the suspects in the second weighing — combining balls suspected of being light, balls suspected of being heavy, and some known good balls. This is essential because, unlike the smaller problems, the defective's direction (heavy or light) is still unknown after the first weighing.

Solution

Show Solution

See answer below

Show Solution

Solution: This weighing problem is another classic brain teaser and is still being asked by many interviewers. The total number of balls often ranges from 8 to more than 100. Here we use n = 12 to show the fundamental approach. The key is to separate the original group (as well as any intermediate subgroups) into three sets instead of two. The reason is that the comparison of the first two groups always gives information about the third group.

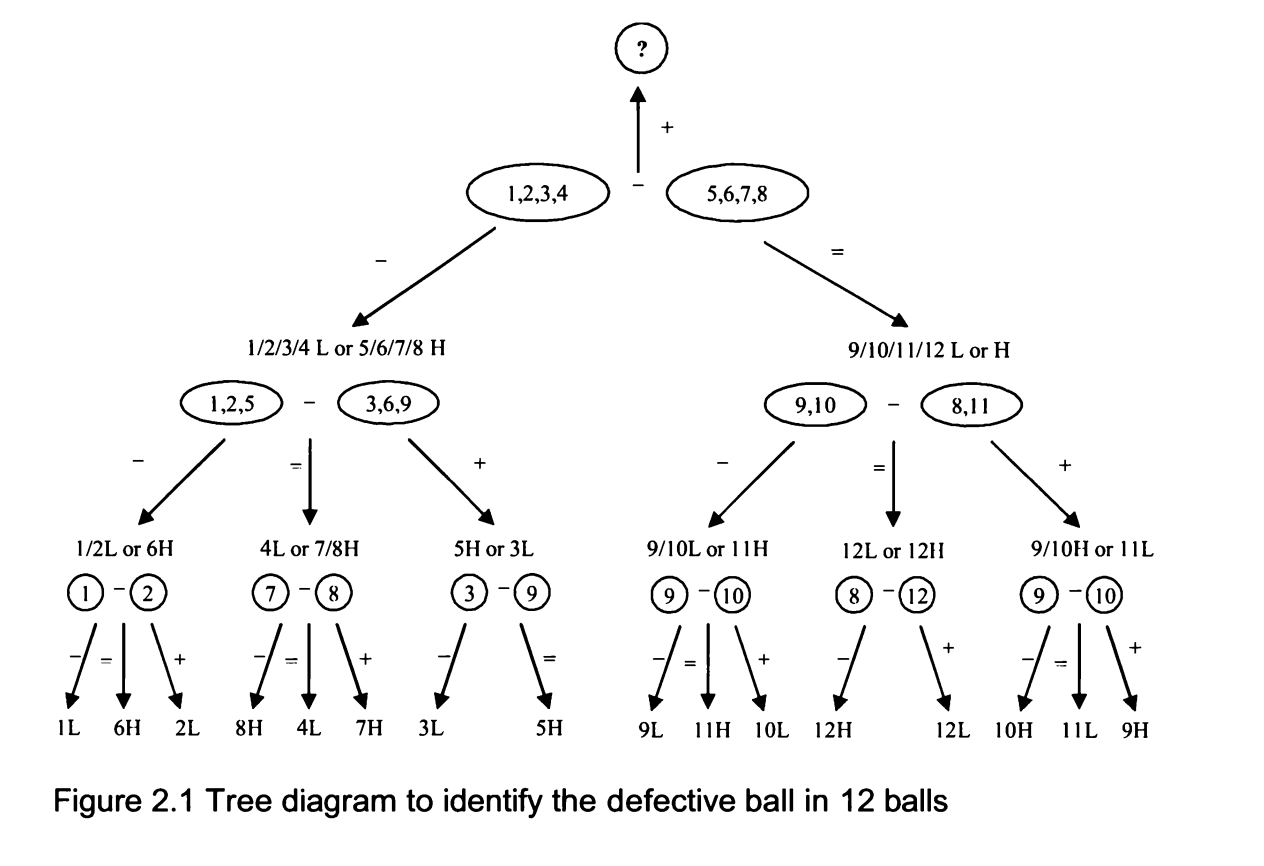

Considering that the solution is wordy to explain, a tree diagram shows the approach in detail. Label the balls 1 through 12 and separate them into three groups with 4 balls each. Weigh balls 1, 2, 3, 4 against balls 5, 6, 7, 8. Then we go on to explore two possible scenarios: two groups balance, as expressed using an "=" sign, or 1, 2, 3, 4 are lighter than 5, 6, 7, 8, as expressed using a "<" sign. There is no need to explain the scenario that 1, 2, 3, 4 are heavier than 5, 6, 7, 8.

(On the above statement, there is no need to explain for the heavier scenario as it is just a matter of symmetry. Nothing makes the 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5, 6, 7, 8 labels special. If 1, 2,3, 4 are heavier than 5, 6, 7, 8, let's just exchange the labels of these two groups. Again we have the case of 1, 2, 3, 4 being lighter than 5, 6, 7, 8.)

If the two groups balance, this immediately tells us that the defective ball is in 9, 10, 11, or 12, and it is either lighter (L) or heavier (H) than other balls. Then we take 9, 10, and 11 from group 3 and compare balls 9, 10 with 8, 11. Here we have already figured out that 8 is a normal ball. If 9, 10 are lighter, it must mean either 9 or 10 is L or 11 is H. In which case, we just compare 9 with 10. If 9 is lighter, 9 is the defective one and it is L; if 9 and 10 balance, then 11 must be defective and H; if 9 is heavier, 10 is the defective one and it is L. If 9, 10 and 8, 11 balance, 12 is the defective one. If 9, 10 is heavier, then either 9 or 10 is H, or 11 is L.

You can easily follow the tree in Figure 2.1 for further analysis, and it is clear from the tree that all possible scenarios can be resolved in 3 measurements.